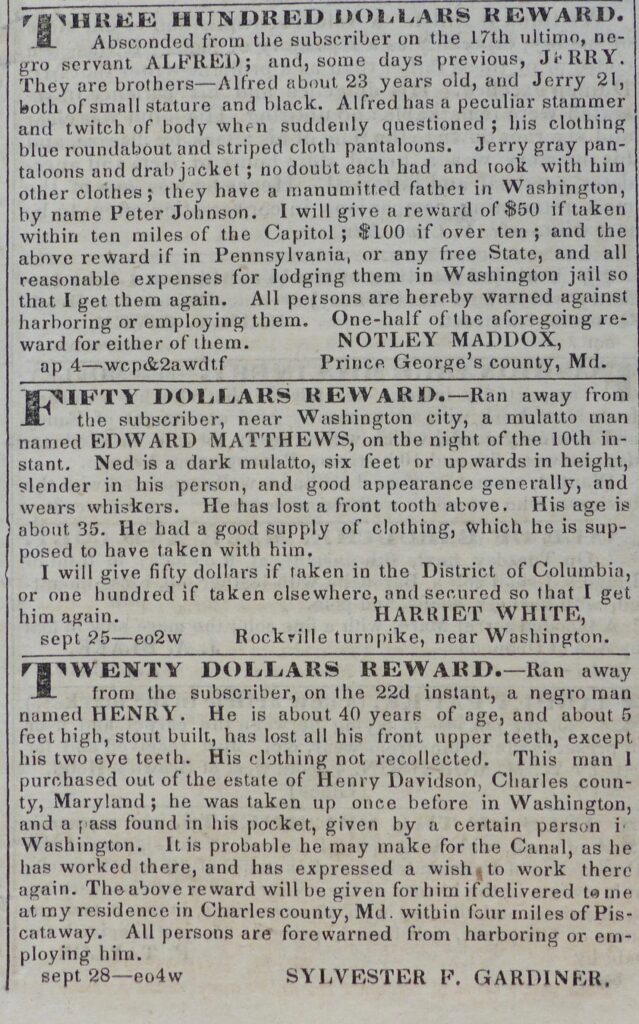

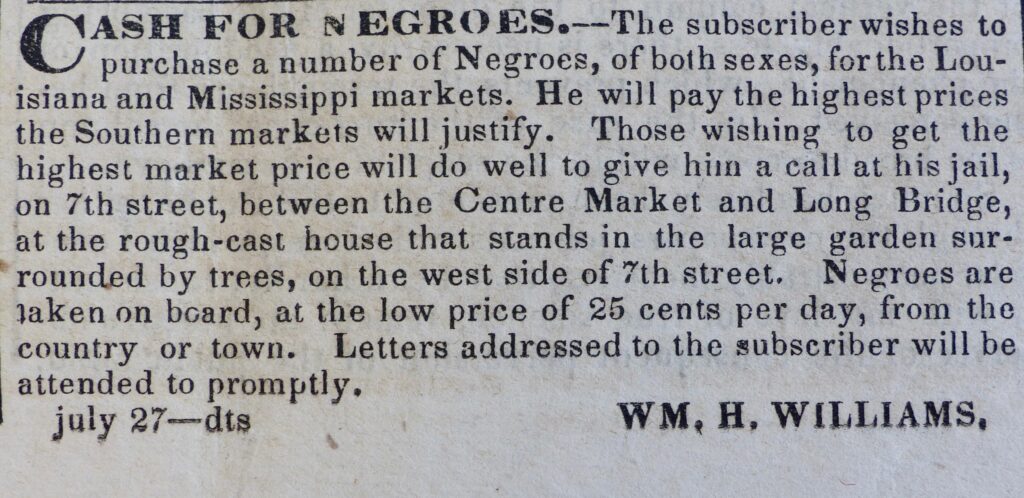

The 19th c. American newspapers in my archives contain a wealth of information on the history of both Liberia colony and sister colonies, created as from 1822, and the independent republic of Liberia, proclaimed on July 26, 1847.

Wikimedia Fred van der Kraaij Collection

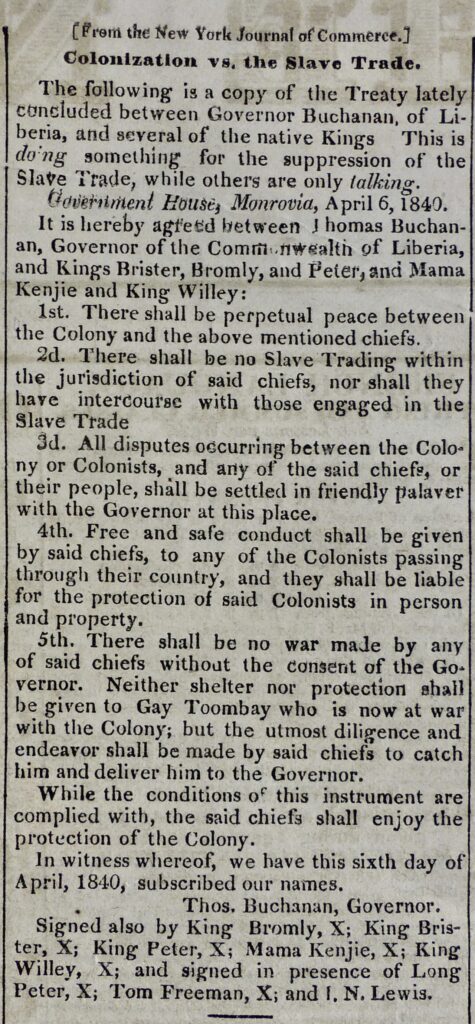

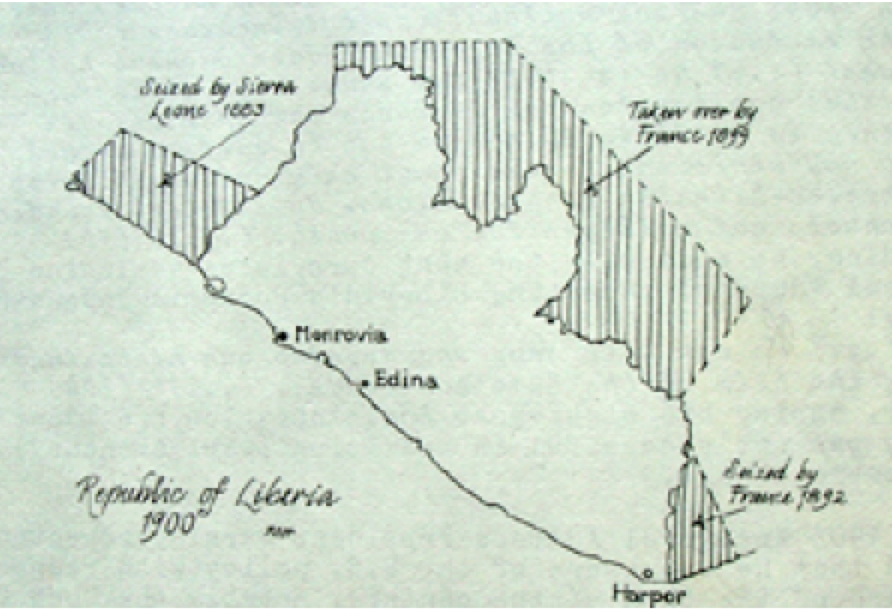

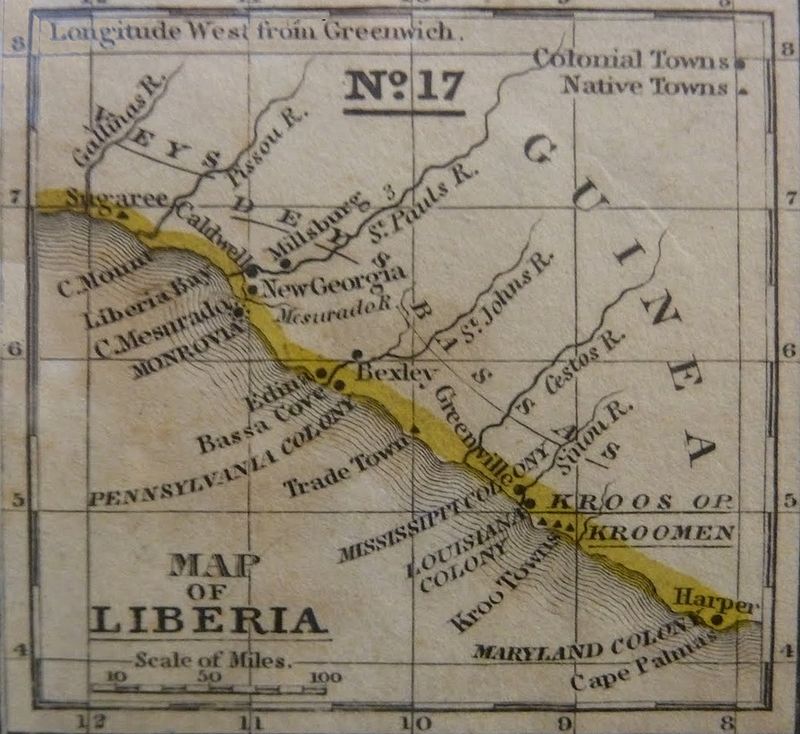

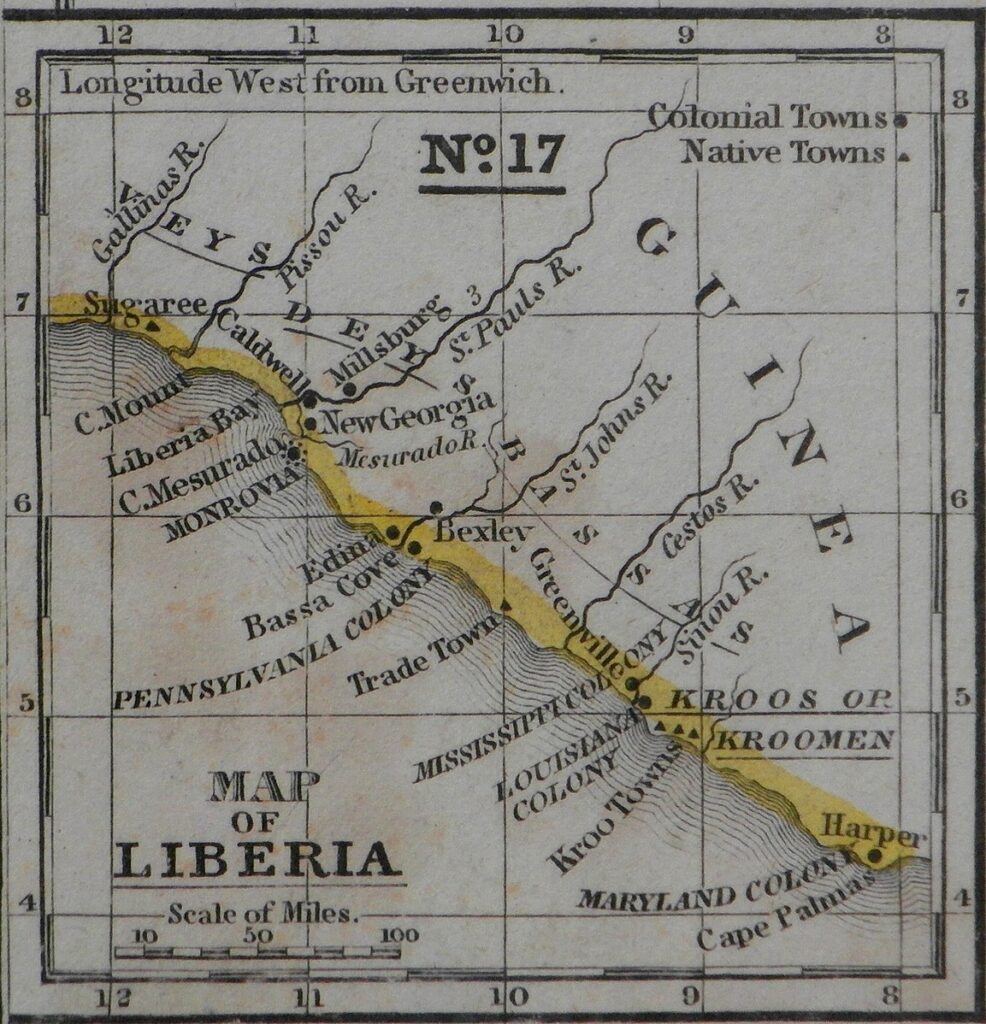

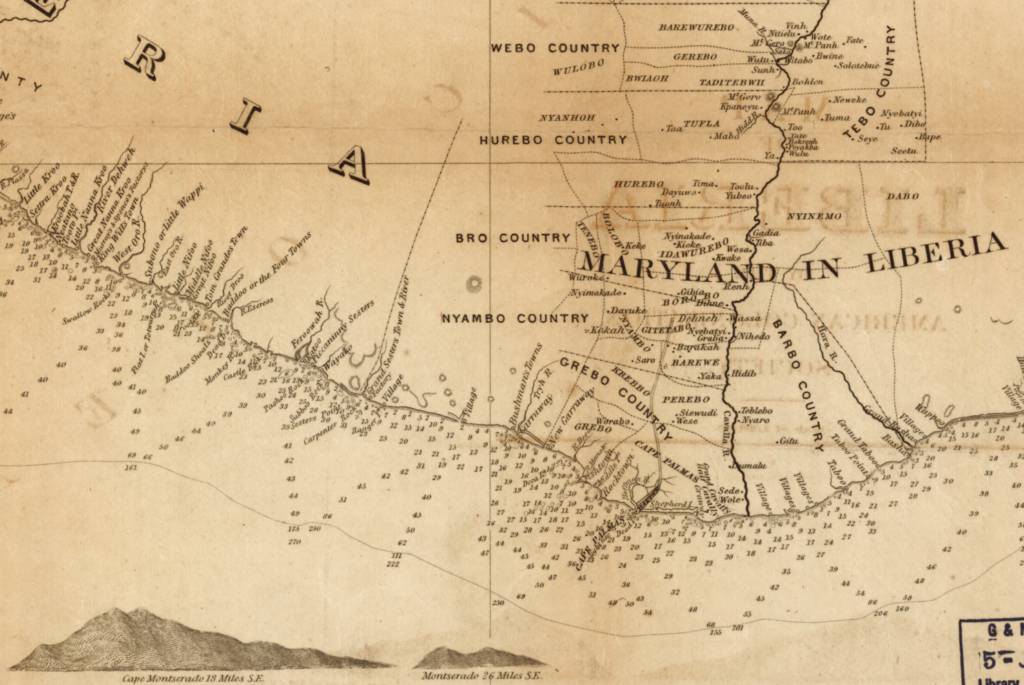

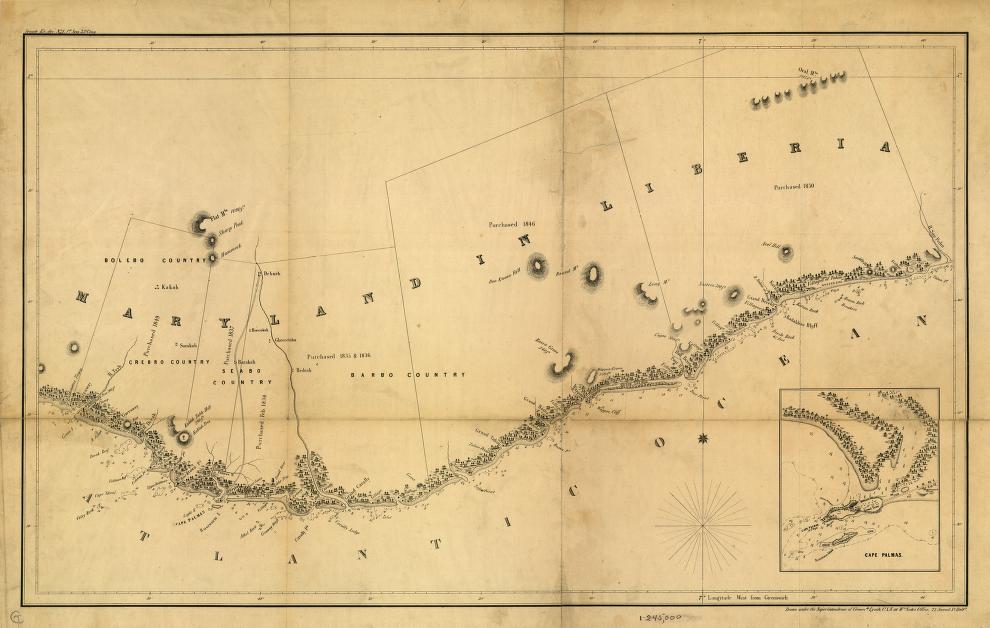

One of the greatest treasures is an article on the colony of Maryland published in 1842, eight years after the first settlement of African-American colonists on Cape Palmas in 1834. Maryland Colony was situated south of the other American colonies such as Pennsylvania Colony, Mississippi Colony, Louisiana Colony, as shown by the Mitchell map of 1839 (above).

The article was originally published in Boston by the Christian Register and Boston Observer on May 21, 1842 and contains a long, detailed and extremely interesting account of a visit of this portion of the western coast of Africa by an unknown traveller. The contents of the article, the details and its diversity perfectly reflect its time and warrant sharing it with a larger public.

Maryland Colony (‘Maryland in Africa’) was a private colony of the Maryland State Colonization Society (an auxiliary of the American Colonization Society) from 1834 till 1854 when it became the independent Republic of Maryland before joining the independent and sovereign republic of Liberia in 1857.

Source: From Colony to Independence: Mid-19th Century Maps of Liberia

Click here for a beautiful, very detailed enlarged version

NB The original text has been reproduced (below) unabridged and unedited – some words and expressions are nowadays considered inappropriate – and as published hence with typographical and linguistic errors.

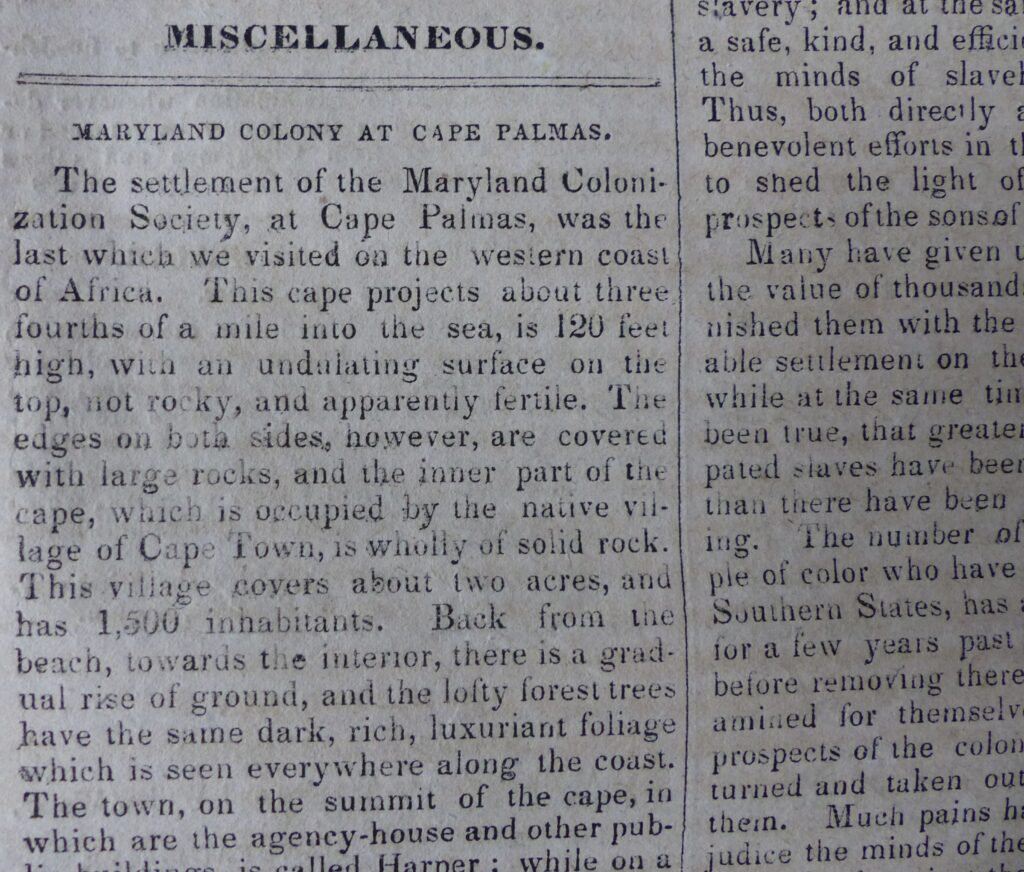

MARYLAND COLONY AT CAPE PALMAS

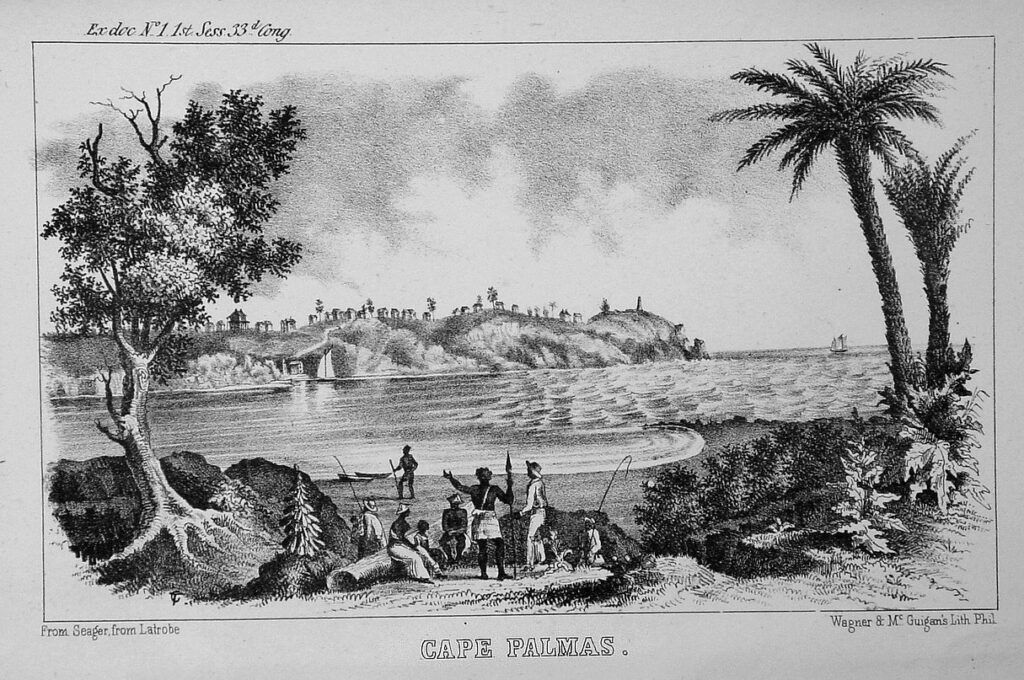

The Settlement of the Maryland Colonization Society, at Cape Palmas, was the last which we visited on the western coast of Africa. This cape projects about three fourths of a mile into the sea, is 120 feet high, with an undulating surface on the top, not rocky, and apparently fertile. The edges on both sides, however, are covered with large rocks, and the inner part of the cape, which is occupied by the native village of Cape Town, is wholly of solid rock. This villages covers about two acres, and has 1,500 inhabitants. Back from the beach, towards the interior, there is a gradual rise of the ground, and the lofty forest trees have the same dark, rich, luxuriant foliage which is seen everywhere along the coast. The town, on the summit of the cape, in which there are the agency-house and other public buildings, is called Harper; while on a fine level spot of ground, half a mile or more from his point, is the town of Latrobe, extending to the sea on the southern side of the cape. These places bear the names of two distinguished citizens of Maryland, who were among the earliest, ablest, and most efficient friends of and advocates of African colonization. One of them has been called from the scenes of his earthly labors, leaving behind him a high reputation for benevolence and philanthropy; while the other, in the full vigor of manhood, is devoting the best energies of his gifted mind and his warm and generous heart to the advancement of that noble cause, which he so early espoused, and which owes so much of its success to his active and perservering efforts for its promotion.

The Maryland colony was founded with the avowed object of entirely freeing the State, from whence its emigrants come, from the evils of slavery; and, with this understanding, received a grant of $200,000 from the Legislature of Maryland. When we were there, it had been in operation three years, and contained 190 inhabitants. There were forty-seven farms, of five acres each, under cultivation; and besides having commenced a public model-farm of fifty acres, the colonists had made five miles of road in the interior, and prepared houses for the accommodation of 900 more emigrants. This colony was founded on the principle of the entire exclusion of ardent spirits; and all trade with the natives is in the hands of the colonial agent, and is carried on for the benefit of the colonial treasury. At Bassa Cove, besides the government store, a few individuals of standing and character are licensed to trade. The object of these restrictions is to check the rage for speculation, which, in the older settlements, has seriously retarded advancement in agriculture and the useful arts. It was also found, that some of the colonists who resided or traveled among the natives in the interior, for the purposes of trade, brought great discredit upon the colony, as well by the gross frauds which they practiced upon the ignorant natives, as by their too ready compliance with the corrupt and licentious habits of savage and barbarous life. Hence it had been thought advisable, in the more recent colonies, to confine the trade with the natives to the hands of a few honest and responsible men; while, at the same time, the colonists are able to obtain such articles as they wish, much cheaper than they could do, were the business of retailing in the hands of a large number of petty traders.

Another error, from which the older colonies have suffered, but against which that at Cape Palmas has been secured, was sending forth indiscriminately, as emigrants, all who were willing to go, without regard to age or sex, or ability by their own efforts to support themselves, and those dependent on them. It is a well-known fact, that on many plantations in the southern United States, not more than one third or one fourth of the slaves are, by their labor, a source of profits for their owners; the rest being either too old or too young to do much for their own support. Now it is obvious, at a single glance, that such a community, with a large proportion of women and children, would be but poorly fitted to act as pioneers in a new settlement, where, in addition to the trial of the constitution by sea-sickness and other exposures of the voyage, together with that of a change of climate, there is also much severe and trying labor demanding in clearing up the dense and lofty forest, in subduing and keeping in subjection the wild and rank luxuriance of the soil, and in erecting suitable dwellings , as well for themselves as for those who might come after them. It were, indeed, almost an act of cruelty, to subject either the aged and infirm, or weak and defenseless women, to such severe trials; while, on the other hand, it is a matter of policy, so far as preventing the increase of the colored race in our own country is concerned, to remove those who are of such an age as to add most rapidly to this class of our population. Children of such parents, too, if born in Africa, will be much better adapted to the peculiar climate of that country than those who even at an early age move thither. Hence it is, that at Monrovia, with a population of six or eight hundred inhabitants, there may now be seen a hundred healthy fine boys, children of the colonists, engaged in their evening gambols in the streets.

In accordance with the views just stated, more than half of the adults in the colony at Cape Palmas when we were there, were strong able-bodied men. The result of this, together with the fact, that the colonists have devoted themselves entirely to agriculture and public improvements, to the neglect of trade, has been a thorough cultivation of the soil, and a degree of advancement and of solid prosperity, such as the most sanguine friends of the colony could, at its commencement, have hardly anticipated. And here the remark is obvious, that the more efficient, intelligent, and virtuous the founders of the first colony are, the sooner will it be prepared safely to receive all, of every class, who may wish to connect themselves with it. Nor can we too highly commend those planters at the South, who, in opposition alike to the weak and misguided zeal of one portion of their fellow-citizens, and the sensitive jealousy and headlong, overbearing rashness of another, are engaged in active and efficient efforts to educate their slaves, with a view to their becoming, in the end, useful, intelligent, and virtuous citizens of Africa.

The fact, that a large and continually increasing proportion of those sent to Liberia, have been slaves, who were emancipated for this very purpose, has awakened extensively, at the South, a spirit of reflection and inquiry as to the whole subject of slavery; and at the same time, has opened a safe, kind, and efficient way of acting on the minds of slaveholders themselves. Thus, both directly and indirectly, have benevolent efforts in this cause done much to shed the lights of hope on the future prospect of the sons of bondage in our midst.

Many have given up all their slaves, to the value of thousands of dollars, and furnished them with the means of a comfortable settlement on the shores of Liberia; while at the same time it is, and long has been true, that greater numbers of emancipated slaves have been offered as emigrants than there have been means for transportation. The number of intelligent free people of color who have emigrated from the Southern States, has also been increasing for a few years past; and some of these, before removing there, have gone and examined for themselves the condition and prospects of the colony, and have then returned and taken out their family with them. Much pains has been taken to prejudice the minds of free people of color in our land against the plan of emigrating to Africa; and, in doing this, not only have frightful stories of death by starvation and disease been fabricated and widely circulated, but many more have been induced to believe that there is no place such as Liberia, and that those who are carried from this country are taken to some foreign land and sold as slaves. The groundless prejudices, however, are rapidly fleeing away before the light of truth; so that, in a recent expedition from Maryland to Cape Palmas, 150 free people of color offered themselves as emigrants; of whom, but 80 could then be furnished with the means of transportation. As colored persons at the South often holds stations of trust in stores and on plantations, and are thus trained to regular business habits, it is not strange that many of the most intelligent, wealthy, and useful of the colonists of Liberia, have come from the slaveholding South.

The Maryland Society, at first, purchased at Cape Palmas, a territory of about twenty square miles, containing a native population of 3,000 or 4,000 souls. Two years afterwards, however, they held deeds from the natives of a tract of country, of from 600 to 800 square miles in extent, including the dominions of nine kings, who were bound to the colony by a league of offensive and defensive. This territory extends along both sides of the Cavalry river, from the ocean to the town of Netea, thirty miles from its mouth. This region of the country is said to be of inexhaustible fertility, beautiful in the extreme in appearance, and thickly peopled by a population on good terms with the colonists, and anxious to enter into treaties with them, for the purpose of having schools established among them, and enjoying the benefits of trade with the colony.

Directly on the coast, in the vicinity of Cape Palmas, and within an extent of twenty miles, there is a native population of 25,000, all of one tribe and speaking the same language, while the arc of a circle extending fifty miles inland from the Cape, would embrace 60,000 or 70,000 natives, all of whom are desirous of the advantages of colonial trade, and the benefits of civilization and Christianity. The treaties made with the natives, secure to them free trade with the colony; protection from the incursions of surrounding tribes, freedom of the evils of the slave-trade , with the obligation on their part to furnish no supplies of rice or other provisions for slave-ships,; and to deliver up for punishment those of their own number, who may in any way be engaged in the slave-trade; and the establishment of schools among them, as soon as practicable.

Efforts were made at an early period, by the colonial government, for the suppression of theft, and other vices which were prevalent among the natives. At first, the tribe to which the thieves belonged, were compelled to make restitution for stolen articles, but as difficulties arose for this course, King Freeman, the native chief in the immediate vicinity of the colony, sent one of his headman to the United States, to see if all that what was told them with regard to America were true , and if so, to bring back with him a code of laws from the Maryland Society, for the government of his tribe. This messenger, with whom we met after his return, was a very shrewd and intelligent person. He was much pleased with his visit to our country, and as, on one occasion, he stood on the lofty monument which overlooks the city of Baltimore, gazing with astonishment on the dense and massive structures below, – on the ships and steamboats, which were speeding their way over the ocean, – the long train of cars, which, as if moved by some unseen spirit, were flying with wings of fire along their iron tracks, and the thousand other mysterious results of human power, as aided by science and arts; – as all these mighty wonders broke in upon the darkness of his savage mind, he exclaimed, in the broken English which he used, ‘Man no make him; God make him.’

The code of law which he wished, was drawn up and explained to him, and though at first he objected to the law forbidding polygamy, on the ground that he had four wives, and that if he turned off part of them they must suffer from want of food, still, he at length approved of it, as a good law for those who were yet unmarried. On his return, these laws were approved by the king; and, as enforced by justices of the peace and constables, chosen both from the natives and the colonists, they have almost entirely suppressed, among his subjects, theft and other troublesome vices, to which they were formerly addicted.

A brother of King Freeman, who came off with his majesty to visit our ship, was pointed out to me as a man of superior talents; and his high massive forehead, and large well-formed head, presented no unworthy model for the demonstrations of a phrenologist. At a single sitting, he learned the English alphabet, and in three weeks had read, and was familiar with, the code of laws referred to above, and thenceforth was constantly consulted by his tribe on all legal questions which arose among them. Mr. Wilson, speaking of the condition of the mission schools under his care at the time we were in Africa, says, ‘We have now about 100 children under instruction. Their progress is most satisfactory. We should have a large adult class, if we were able to teach it, and although I have declined it for the present, I have been constrained, by the importunity of two men, to take them into my study. One of these, is the brother of King Freeman, and a very influential man with his people, and decidedly the most talented native I have ever known. The other is the man who recently visited Baltimore. Of the former, I have high hopes of usefulness. His progress in learning, so far, is unequalled by any thing I have ever known, either in America or in Africa.’ The fact, that this man has since become an enlightened and consistent member of the Christian church, is one of much interest to the benevolent mind.

King Freeman came off to visit our ship in a large war canoe, with the colonial flag flying, and attended by a number of his head men. He was much astonished, on beholding the big guns, and the drilling of the marines, though at the time, like other great men, he strove to conceal his emotions for fear of lowering his dignity, or of being thought ignorant of the wonders of the world. The colonial agent stated that afterward, when describing what he saw, the cold sweat stood on his brow, and as our ship was much larger than any he had seen before, it gave him greatly enlarged ideas of our national power and greatness. The effect of such an exhibition is to lead the native tribes to be anxious to enter into treaties of alliance with the colonists, as a means of protection, and for purposes of trade, and also, through fear of the consequences, to restrain them from violating such treaties as already exist.

King Freeman is apparently about sixty years of age, of a tall, athletic form, and a sedate, but intelligent expression of countenance. He wore a hat, and, like other natives, had a strip of cloth about the loins. His otherwise naked body, was wrapped in a royal bode, which truly made him the admired of all the admirers. This was nothing else than a large and gorgeous calico bedquilt, in which bright scarlet was the prevailing color, and, considering the source from whence it came, he might well be proud of it; for the fair ladies of Baltimore, (and none are fairer,) had sent out this highly wrought and beautiful specimen of their handiwork, as a token of their esteem for his sable majesty, in having so kindly furnished an asylum and a resting-place, for the sons of bondage, who had gone forth from their midst. Still, as he gathered up it ample folds around him, and as it dropped from his shoulders, released now this hand and then the other to replace it, or was aided by his followers in supporting and adjusting it, it cannot be denied that his appearance was somewhat ludicrous. As his bare black legs were seen beneath this gaudy covering, his resemblance to a peacock was such as might readily suggest itself to the mind; nor were it strange, if the sailors, with their ready wit, and their love of fun, should suggest, that his Highness must have been either greatly in a hurry, or half seas over, when he rose in the morning, thus to mistake his bedclothes for his breeches. In the train of the king, was a specimen of female royalty, some sixteen years of age, and who, when wine was offered her, refused to taste of it, through fear of being poisoned, as this mode of disposing of obnoxious individuals is said to be quite common among the natives.

Another visitor who honored us with his presence, was King War, who is at the head of a powerful tribe about forty miles in the interior. He wore over his shoulders a calico shawl, with broad alternate stripes of red and black. The motion of the ship made him sea-sick, and there may, too, have been some whisky in the case, and so, to refresh himself, he laid down on a blanket beside one of the guns, and took a nap. Alas for royalty !

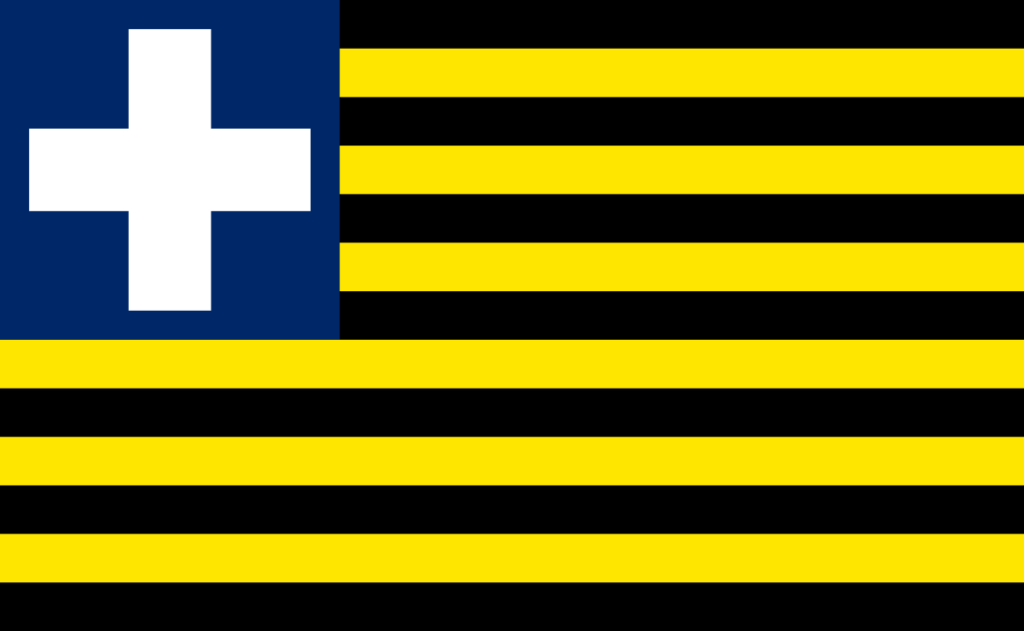

(illustration added, not included in the 1842 newspaper article)

The agent or Governor of the Maryland Colony, Mr. J.B. Russwurm, is a man of color, having, to judge from his complexion, bout equal proportions of white and black blood in his veins. He was educated at one of our northern colleges; and as at that time the efforts of the pretended friends of the colored race, rashly to force public opinion into the channel which they had marked out for it, had not, by their natural reaction, caused their rights and feelings to be less respected than before, he was treated with peculiar kindness and consideration, as well for his superior talents and acquirements, as well peculiarly modest, amiable, and gentlemanly manners and department. After completing his education, he was for a time editor of an abolition paper in the city of New York, until, perceiving the evil tendency of the doctrines he had taught, he openly abjured and denounced them in his paper, because a strong and decided friend of colonization, emigrated to Africa, married there, and for ten years had been the senior member of the first commercial house at Monrovia, when he was appointed to the office which he now holds.

As both the natives and the colonists have been accustomed to regard white men with far more deference and respect than those of their own complexion, the policy of placing a colored man at the head of the colony was by some regarded as questionable; still, as it is expected that the colonists will in the end take care of themselves, it has been thought that the sooner they are trained in habits of self-governance, the better. A case of serious collision between the colonists and the natives had arisen, caused by the arrest and the imprisonment of one of the more aged natives, on the charge of theft. In this instance, however, the great personal influence of our missionary, Mr. Wilson, and the high veneration which the natives have for him, enabled him to restrain them from going to extremes. The colonists were thus taught a useful lesson, as to tempering energy with due discretion, in their efforts to subject to the restrains of law those untamed children of nature.

Of the beneficial influence of the kind and judicious application of legal restraints to the natives and suppressing vice and crime among them, I have already spoken. They have also been excited to greatly increased exertion in the cultivation of the soil, from witnessing the success of the colonists, as also from the fact, that so convenient a market is opened as well for their cattle and other live stock, as for rice and other fruits of the earth. Their natural desire to obtain such articles of comfort or of luxury as they see in the possession of the colonists, also acts as a powerful stimulus to excite them to increased effort, that thus they may have the means of enjoying in some degree the blessings of civilized life.

When we were at Cape Palmas, there were missionaries of the United States of four different religious denominations, stationed there. To each of these the Maryland Society has given several acres of land, and buildings had been erected for dwelling-houses and schools, at the expense of the respective societies by which the missionaries were sent out. Those of the American Board, occupied by Mr. Wilson, consisting of a large school-house and dormitory for the scholars, are near the sea, a short distance from the cape, and were in full view from our ship. Mr. and Mrs. Wilson were both from the southern states, and, from their knowledge of the habits and character of the colored race, were well fitted for their field of labor. They had at time about 100 children under their care, and six little native girls came on board our ship with them. In 1841, there was preaching at 6 stations: there were 23 church-members ; 125 in the schools, and 18 missionaries and assistants, including a physician and printer. Though their pupils were taken wild from the woods, yet Mrs. W. observed to me, that, by treating them with marked kindness and attention, she never failed strongly to attach them to her, and to bring them under her influence in the course of a single week. The whole expense of feeding and clothing these children, is about fifteen dollars a year each. They have a kind of police among themselves; so that, when one of them does wrong, he is speedily arrested by the proper officer, and brought to justice. To see a lady like Mrs. W., born to affluence, accustomed to move in the highest circles in one of our large cities, possessed of a handsome fortune, and yet among savages in a sickly clinic, and far removed from all refined social intercourse of her early days, devoting her energies to the self-denying task of elevating the poor degraded African from the deep degradation of paganism, – to see such an one thus employed, presents in the strongest light the power of a Christian faith, in triumphing over the selfish tendencies of our nature, giving to woman’s loveliness an angel’s zeal, and sending her forth, as a ministering spirit, on an errand of mercy to the lost and the perishing. – Rockwell’s Foreign Travel and Life at Sea.

Source: Maryland Colony at Cape Palmas, in: Christian Register and Boston Recorder, Boston, Saturday, May 21, 1842, Vol. XXI, No. 21, p. 4, columns 1-4 (under the heading ‘MISCELLANEOUS’)

Recommended reading:

From Colony to Independence: Mid-19th century maps of Liberia;

August 9, 2017; posted by Tim St. Onge (Library of Congress).

American Colonization Society (Wikipedia)

Maryland State Colonization Society (Wikipedia)

Republic of Maryland (Wikipedia)

Maryland in Liberia: Liberia History (Access Genealogy – A Free Genealogy Website)

Tracing the Travels of Maryland’s African-Americans (Maryland Center for History and Culture)